Like every emerging solar trend, “perovskite” technology has been discussed in research circles for many years, but now it seems to be picking up steam. The new thin-film technology could bring increased efficiency at a lower cost to solar manufacturing, if it could just get out of the laboratory phase.

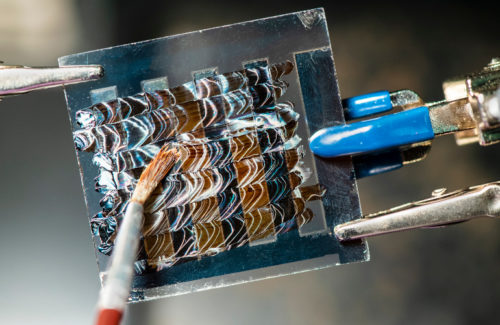

A perovskite cell using methylammonium lead triiodide thin films. (Photo by Dennis Schroeder / NREL)

A perovskite is any type of material that has the same crystal structure as calcium titanium oxide (CaTiO3). The general chemical formula for perovskite compounds is ABX3 — where A and B are cations and X is the bonding anion (see how it looks like CaTiO3?). Within solar, lead is often the dominant metal used in perovskites.

Since silicon isn’t involved, a perovskite solar cell is considered thin-film technology. And because it uses abundant and inexpensive materials (see: lead), perovskite has the potential to become the dominant thin-film — and possibly overall — solar manufacturing technology.

In lab settings, perovskite cells are made by depositing chemicals by spin-coating, spraying or “painting” them onto a substrate. The perovskite material forms as the chemicals crystallize. Easy application by painting onto substrates opens perovskite’s potential in markets wanting flexible, lightweight and non-uniform solar generation options. Although it has shown excellent performance potential in the lab (efficiency has increased from 12% to over 23% in just four years), the issue with perovskite is that its efficiency declines quickly as the module size increases. NREL has spent considerable research time on perovskite to prove the material’s effectiveness at solar conversion. The research lab attributes the decline in performance to the non-uniform coating of chemicals in the cell and conversion losses when perovskite is layered with other solar cell technologies.

NREL researchers have developed an interdigitated back contact solar cell design in which the metals and transport materials are solution-processed by either ink jet or spray coating. Combined with a perovskite ink formulation with a low boiling point allows “paintable” solar cells. (Photo by Dennis Schroeder / NREL)

In fact, labs have found promising success with perovskite when it works in tandem with other solar technologies. Perovskites absorb more of the light spectrum, so that layer is placed on top of a successfully stable material. CIGS-perovskite tandem cells are a popular testing choice and have made big gains, from 17.8% efficiency in late 2016 to 21.5% in January 2019. And since CIGS thin-film already has success at scale, improving perovskite’s performance in tandem may be easier than working on the new technology alone. Pairing perovskite with silicon is also not out of the question. Researchers at imec think a silicon-perovskite stacked cell could easily push 30% efficiency.

NREL is fully on board with guiding perovskite’s mainstream adoption. During a recent study, the lab found that a solo perovskite cell held on to 94% of its starting efficiency after 1,000 hours of continuous light exposure. While more testing is required to see if the cells could survive normal panel lifetimes of 20+ years, the study released in 2018 determines that perovskite solar cells are very stable on their own. The industry just needs to figure out how to scale up.

My product is a peel and stick nonskid. We spray alum oxide and aluminum to a wire mesh. The US Navy uses it on ships. If I could paint a solar layer it may melt the snow and ice from my products surface. This would be ideal for ship decks in cold climates.

As your last paragraph clearly implies, the perovskite cell lifetime is a major issue. I would have appreciated a little more perspective on lifetime than a reference to a reference article (intro is all that is publically available free) that starts with “The perovskite absorber material itself has been heavily scrutinized for being prone to degradation by water, oxygen and ultraviolet light. ” It’s about a 1000 hr test (~1/4 of a year of light?!) of unencapsulated perovskite with no translation to actual panel lifetime.

This implies that even with a nice “achieved 22.7% efficiency.” the technology is at least a decade away from residential rooftop products.